MGH Personal Space Behavioral Study

A study into personal space, and how much encroachment into it different people will accept, created for Massachusetts General Hospital’s Department of Psychiatry.

Contributions: concept design, Unity development, environment design, sound design

The Science of Virtual Reality

There is, unsurprisingly, very little in the way of “actual” scientific data about virtual, augmented, or mixed reality. There is actually remarkably little such data about almost all modern technology, but XR being on the cutting edge exacerbates the problem dramatically.

So it was very intriguing when I was approached by the Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Department to help them with a study about personal space and how patients with various disorders regard their own “bubble”. The MGH team was interested in using VR to make an otherwise-difficult experiment more straightforward (human interaction is notoriously hard to replicate), and I was interested in being part of one of the first scientific studies to actually leverage virtual reality.

(Note: this experiment has not yet been concluded, and so some information has been withheld while it is ongoing.)

Just Ignore the Uncanny Valley

In digital media and robotics, the “uncanny valley” is the term used to describe a human-like actor that is so close to being “100% human” that the most minute distinctions are magnified in an observer’s mind a thousand-fold. This creates a “valley” of perception where something which is “99%” human-like is perceived much more negatively than something that is only “90%” human-like.

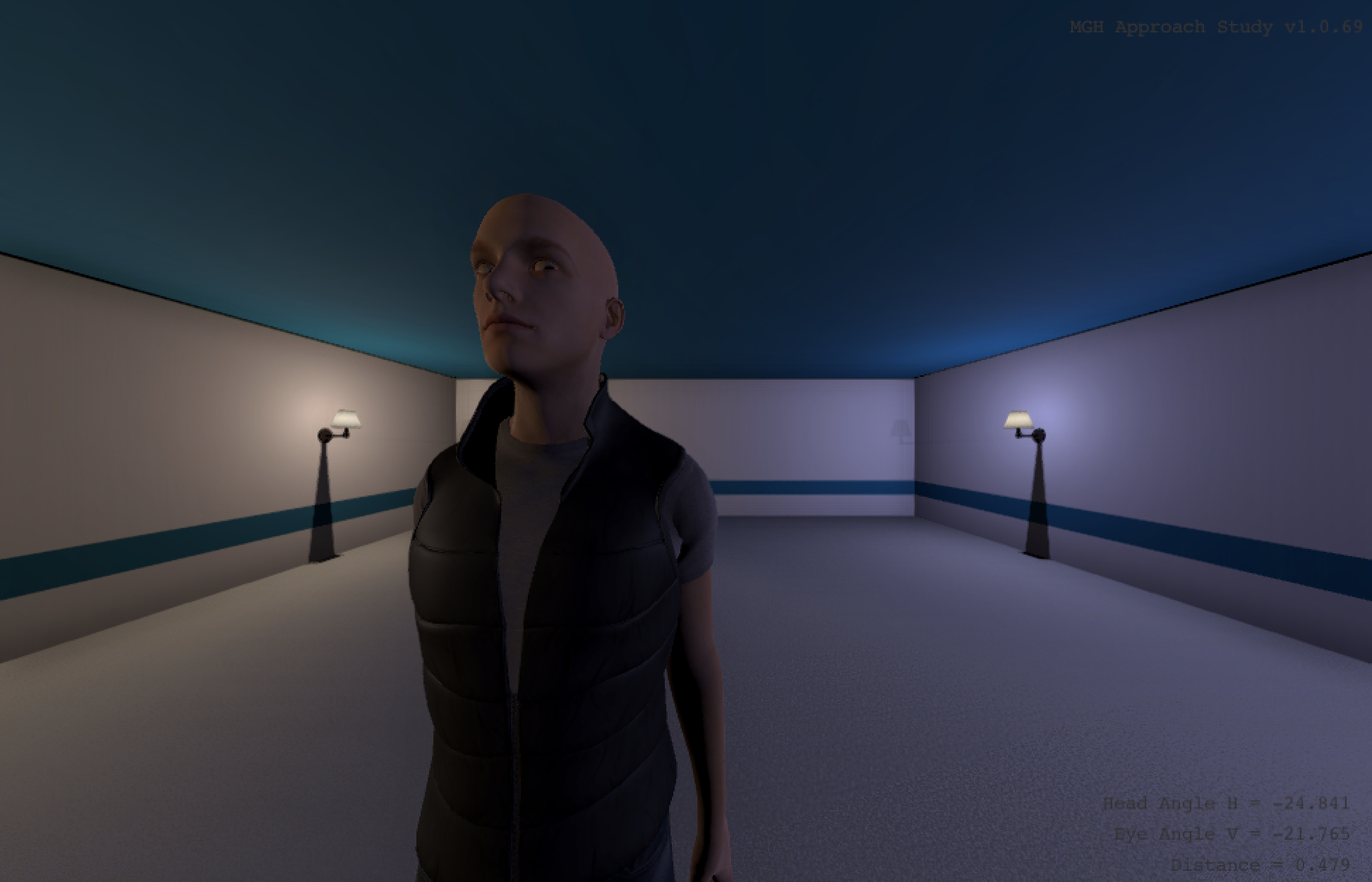

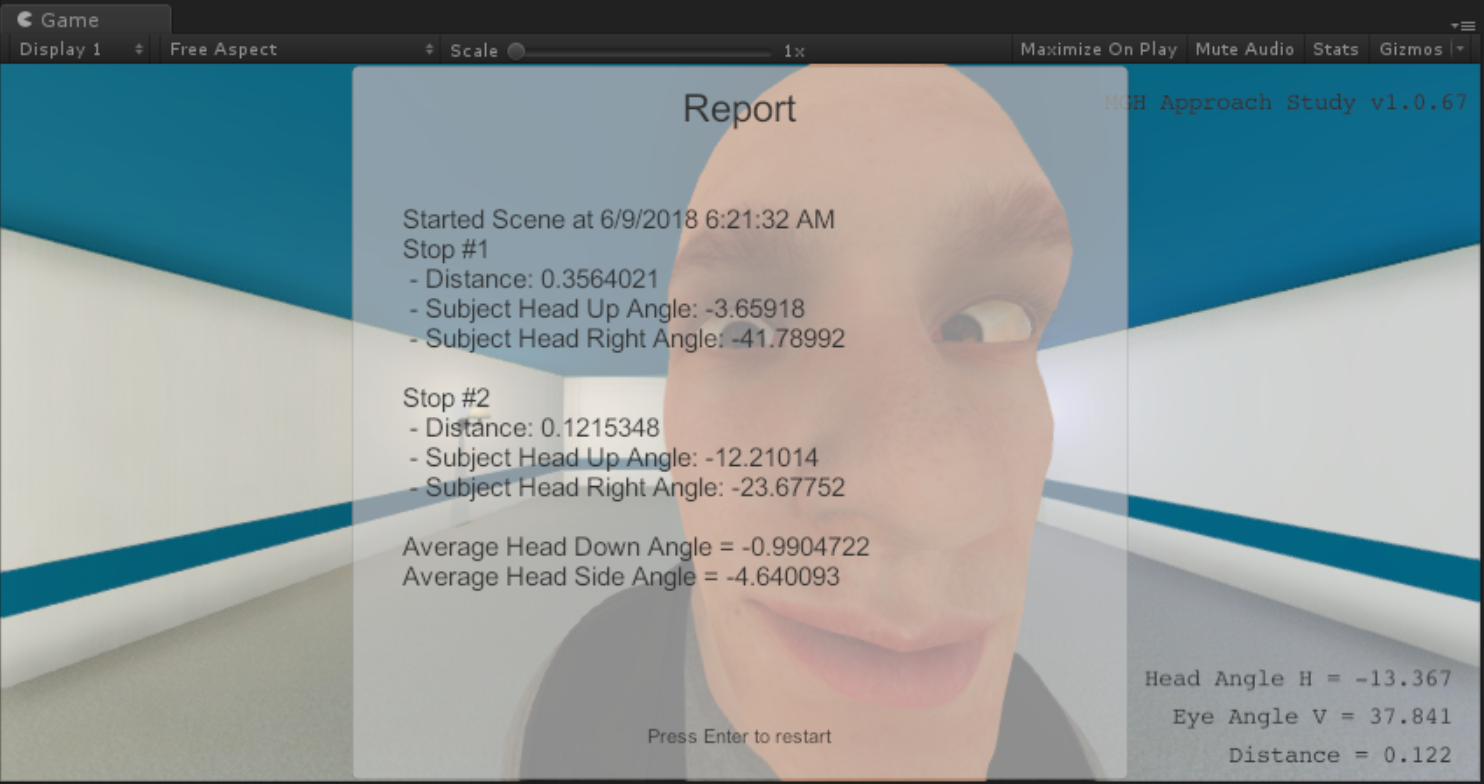

The premise of the MGH team’s study was that in “normal” human interaction, most people have a “personal bubble” which, when crossed, creates discomfort. For varying psychiatric disorders, they theorized that this bubble might grow or shrink based on the specific disorder.

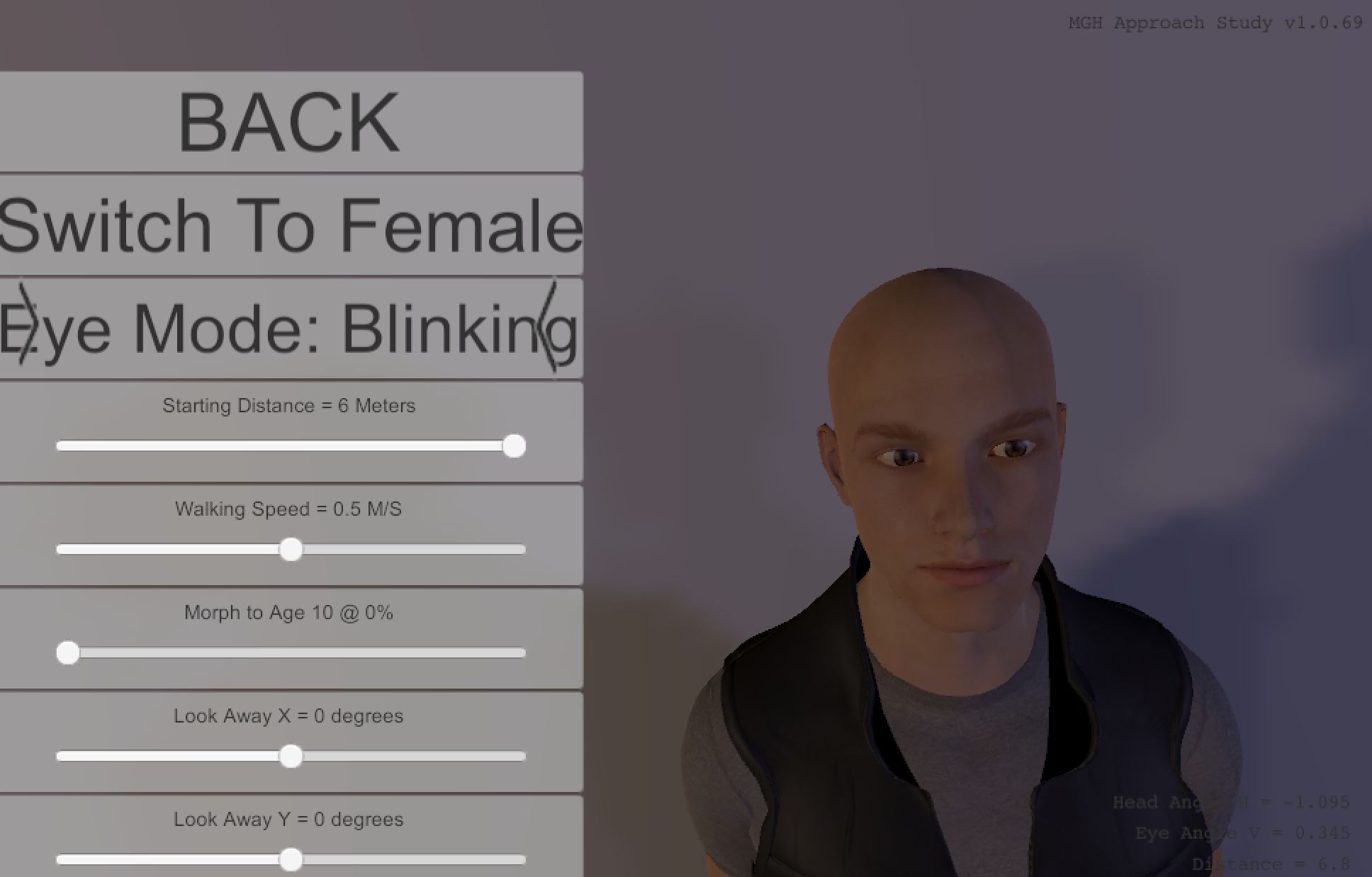

After informing the MGH team of the uncanny valley problem, I offered a possible solution. If we could demonstrate that something which was not yet in the uncanny valley (the 90% human-like example) could provoke the same discomfort reactions in VR that an actual human does in reality, it would not matter if the subject perceived the virtual actor as human.

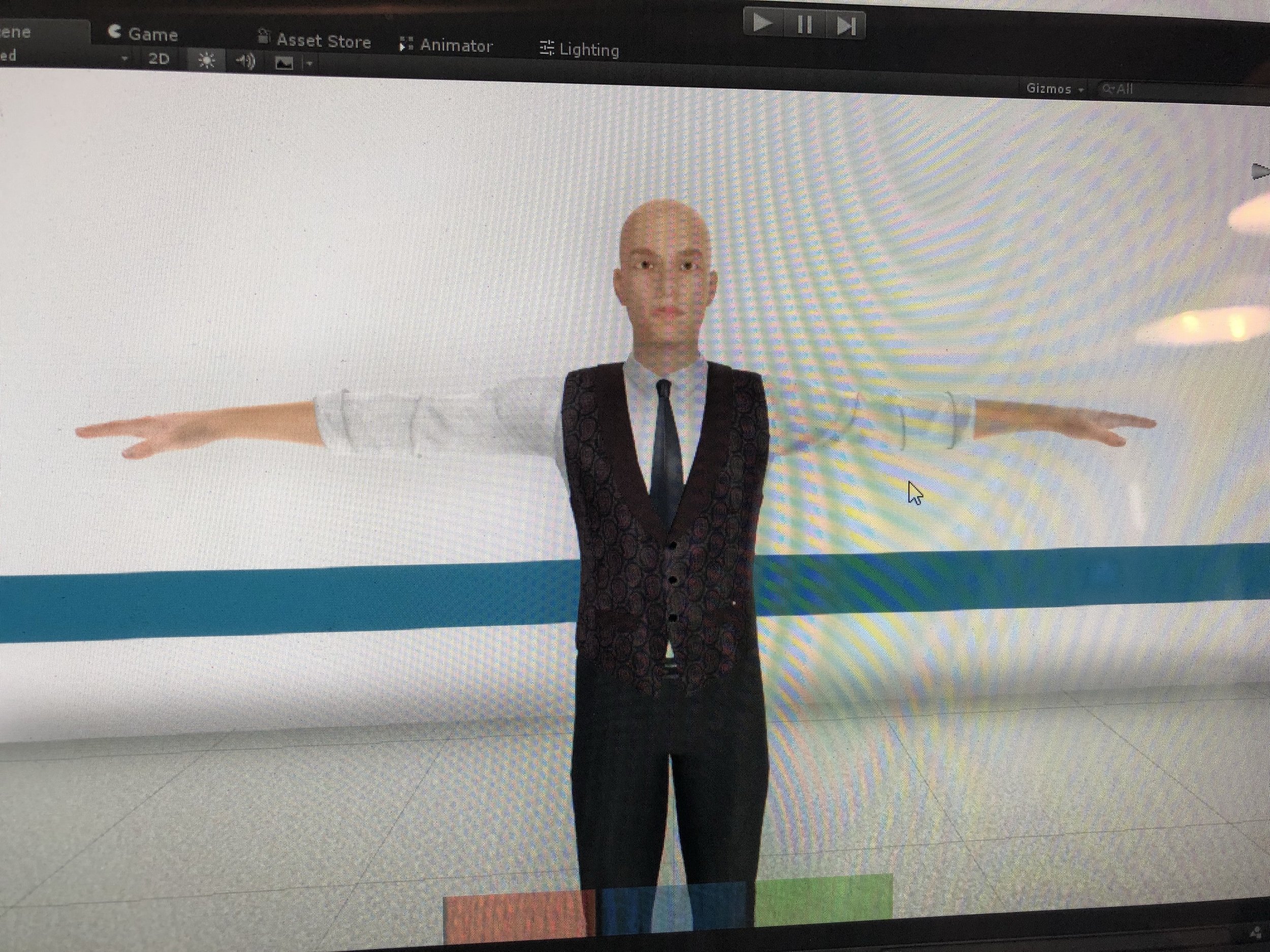

A bit of testing with moderately- but not perfectly-accurate human characters later, we had landed on a workaround and a way forward, and proceeded with creating a variety of “90% human-like” avatars.

Science Is Cool!

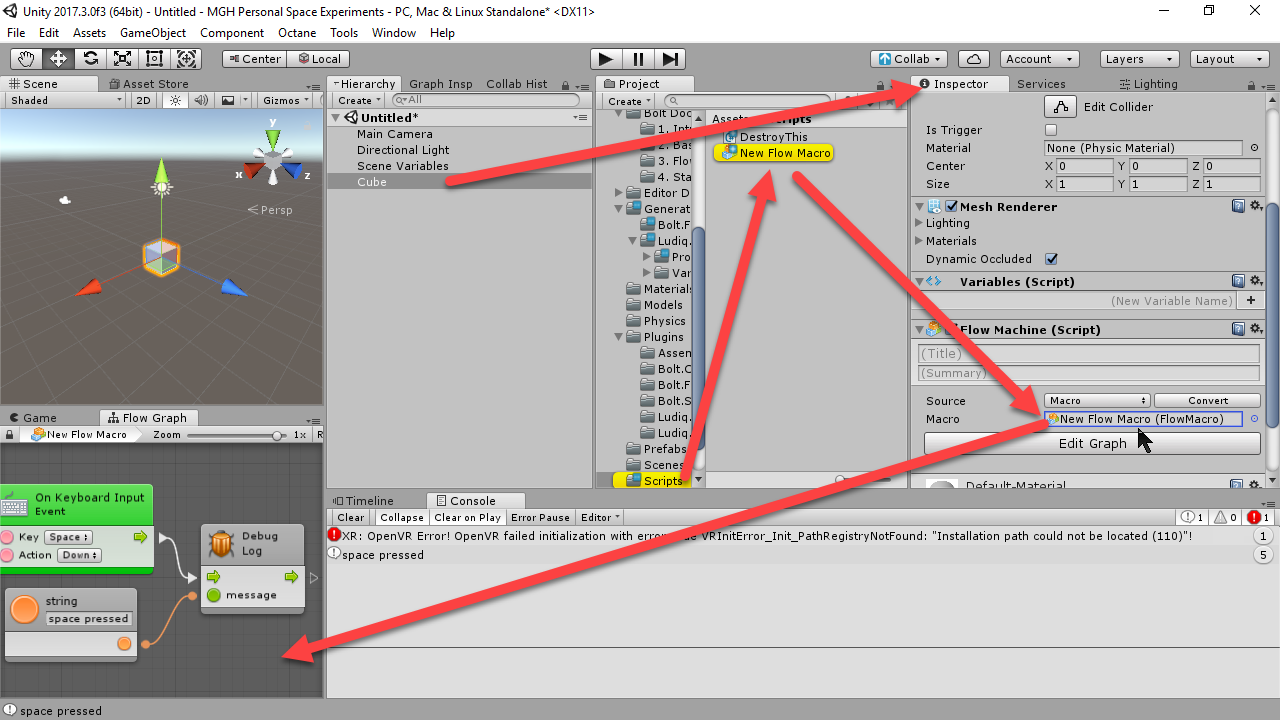

Though this experiment is ongoing, the development portion is mostly completed.

Creating a VR experience that will (hopefully) stand up to the rigors necessary of proper scientific experimentation was an interesting process, and a reminder that for these new industries to recognize their true potential (in the way that 3D graphics and computers have), those of us who are familiar with them and want them to succeed will need to find novel ways to address problems outside of our areas of comfort.

I have no scientific background, but by working with a team which did, we were together able to adapt a technology that is still (unfortunately) scoffed at as being “only for games” into something that could genuinely help advance an important field, and hopefully even help a lot of people.

And yes, I did get to design some genuinely unnerving virtual characters and locations in the meantime. Bonus!